August is the month of our greatest works in progress. It opens on Emancipation Day, August 1, and closes on Independence Day, August 31, which came out of the collapse of the West Indian Federation.

Interestingly, our anthem followed the same trajectory, starting with British Guiana-born Pat Castagne’s song for the Federation which opened with: “Forged from the depths of slavery.”

Jamaica abandoned that Federal experiment, followed by Trinidad & Tobago. The dream of regional unity languished, and both countries rushed to independence. Jamaica got a Pentecostal-type anthem: “Eternal Father bless our land/Guard us with thy mighty hand.”

And Castagne retooled his Federal song for an independent T&T, swapping “the depths of slavery” for “the love of liberty” but leaving the rest intact – which was unfortunate because the words don’t make sense. Think of it: “Forged from the love of liberty, in the fires of hope and prayer/With boundless faith in our destiny, we solemnly declare/Side by side we stand…”

Then what? Whose love of liberty has been shaped by fire? Who are so confident in their future, they are declaring in a formal and dignified way that they stand side by side? You’d assume it was we the people. But you’d be wrong.

They are: “Islands of the blue Caribbean Sea.”

In other words, Trinidad, Tobago, Monos, Gasparee, Huevos, Chacachacare, the Five Islands, Paradise Island, and smaller rocks protruding from the ocean, such as Centipede Island and Saut D’Eau Island are the ones making solemn declarations about standing side by side: “We pledge our lives to thee”.

Give me a break. Black Stalin or David Rudder, if they they’d been around at the time, would have done a better job, or one of our poets, Eric Roach for instance. Instead, an advertising copywriter did what they always do: cobbled together a bunch of cool-sounding words for the Federation, which nobody checked if they actually made sense. Then independence entered the agenda, and no one bothered to scrutinize a song that they already knew and which and felt vaguely uplifting and profound.

It is what it is. People are touchy about national poetic licentiousness anyway, so we’d better not go further. Why, only last year I commented in social media on the “Star Spangled Banner” being played on pan at some American sporting event, and I was not at all appreciated.

Someone had likened the performance to when Jimi Hendrix played the anthem back in the day. Now, I have no problem giving our national ego a gentle massage, which was my original intention in posting video – to show how far pan reach. But the comparison to Hendrix pointed the discussion to more fruitful speculation.

It was on August 18, 1969, a year after Martin Luther King’s assassination caused riots in over 100 US cities, when the invasion of Vietnam was raging, that Jimi Hendrix performed the US anthem.

That August morning in the Woodstock Rock Festival, Hendrix launched into a half-hour medley, including “Voodoo Chile” and “Purple Haze”, and in the middle, his long instrumental interpretation of the “Star Spangled Banner”.

He started close to a standard version but at “the rocket’s red glare, the bombs bursting in air” his guitar began to scream like a dive bomber. The next line, “the flag was still there” segued into “Taps”. Then the guitar wailed, like someone in pain. It rumbled like the napalm bombs that set Vietnamese people afire. With the drums it hammered like a machine gun.

Hendrix turned the US anthem into an anti-war scream as appropriate to the 60s as Picasso’s Guernica was to the 30s.

Today I would love to hear an appropriate response to Jimi’s “Star Spangled Banner” on pan, because of Black Lives Matter and especially Colin Kaeperneck’s refusal to stand for the US anthem, because it is a song forged from the love of slavery, a paean to American racism, and because it has a closer connection to T&T than to any other country. You see, we feature in its third verse:

“No refuge could save the hireling and slave/From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave/And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave/O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.”

Those lines defending slavery were written in 1814 by Francis Scott Key shortly after Fort McHenry was bombarded by the Royal Navy in the 1812 British-American War. It refers to those slaves who had fled to join the British army in exchange for the promise of freedom.

Earlier that year Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane, on taking over the command of British forces, had begun recruiting more black soldiers from the enslaved population by having a proclamation distributed in the Chesapeak region:

“All who may be disposed to emigrate from the UNITED STATES will, with their Families, be received on board His Majesty’s Ships or Vessels of War, or at the Military Posts that may be established, upon or near the Coast of the UNITED STATES, when they will have their choice of either entering into His Majesty’s Sea or Land Forces, or of being sent as FREE Settlers to the British Possessions in North America or the West Indies, where they will meet with due encouragement.”

Thousands took up the offer. Most went to Canada and the rest joined the Corps of Colonial Marines along the Atlantic coast; some were stationed in Spanish Florida and some in Bermuda. After the war the Florida fort, referred to as the “Negro Fort” by General Andrew Jackson, was left in the hands of the ex-slaves and their native allies to become a centre of resistance against slavery until it was destroyed in 1816.

Those Africans and Native Americans who chose death before a return to slavery, the hirelings and slaves threatened by Francis Scott Key, truly forged from the love of liberty.

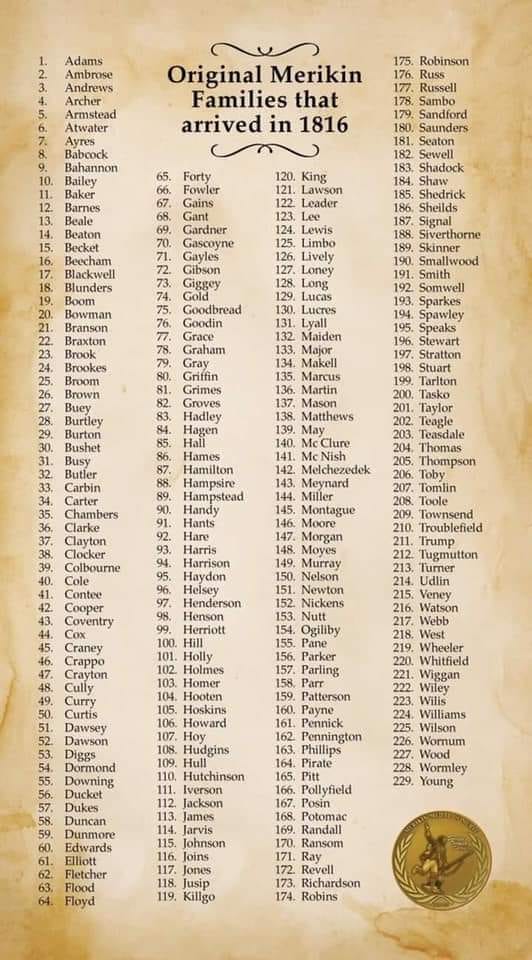

And the other black soldiers based in Bermuda were resettled with their families, 574 men and about 200 women and children, in Trinidad, which was still a British slave colony. Six Company Villages were established by the “Merikins” (Americans) in the dense Moruga forest, every marine receiving 16 acres.

Those black men and women built free communities 20 years before slavery was abolished in Trinidad, and half a century before America’s Emancipation Proclamation. They were the hirelings and slaves Francis Scott Key threatened with the “terror of flight and the gloom of the grave”, but who nonetheless started with subsistence farming and soon moved to producing cash crops. They practiced obeah, herbal medicine and the Baptist religion, which in time evolved into our indigenous Spiritual Baptist belief system.

In Trinidad’s slave society they made the Moruga forest and their six Company Villages the true land of the free and home of the brave.

I appreciate the arc of your story, from slavery in America “land of the free and home of the brave” to living free surviving in the dense South American forests of our small island Trinidad. The contrast that TT must still be thankful for today!

Happy independence day Kim!

LikeLike

DearKim,We must not forget the African American muslims who settled in the Hondo river basin in Valencia whilst the Baptists settled in Moruga.These muslims,joined by soldiers of the disbanded West India regiment,established a thriving settlement in Valencia and were among the foundation members of what later became the T’dad police force.An essential part of our history.Keep up the blog! bs

LikeLike

Yes. I remember you gave a great lecture on that a few years ago, and explained the place names like New Grant and Hard Bargain.

LikeLike

Brinsley, I’ve moved my blog to https://www.santimanitayblog.com/

LikeLike

I’ve moved my blog to https://www.santimanitayblog.com/

LikeLike